Is protest broken?

The Saturday following the 2024 election, a coalition of over 30 progressive groups in New York City organized thousands of people from all walks of life to take to the streets to “protect our futures.”

At least kind of. In reality, there were probably more like one thousand people there, the vast majority of them already part of an organization or a practiced demonstrator, and all of them following a barricaded route chaperoned by the NYPD who, given the cordoned off pens at the rally site that were never filled, were also expecting more than the usual suspects.

In this country’s largest city, with developed civil society infrastructure, and the enormous stakes of a Trump presidency at hand, there’s no way to spin this rally as a meeting of the moment.

This is not an unusual failure. Anyone who has organized in movements has organized protests that have underwhelmed, overwhelmed, or failed to achieve its desired ends (often all three at once). The classic debrief from these experiences asks what the organizers did wrong, and could do better next time, so that more people participate and have a more empowering experience, more people see it in news and online and are drawn to our cause, and our opponents are provoked into mistakes or forced into concessions. There are always some lessons.

And yet: given the frequency of this frustration and the stakes of our (in)action, I’m wondering if there may be a broader insight not from a single event, but from interrogating our theory of protest as a whole.

Our theory of protest

I use “protest” here as shorthand for many kinds of non-violent direct action, all of which are aimed, in some way, to change some decisionmaker’s posture away from the status quo. This may include rallies, marches, walkouts, strikes, boycotts, and many other things you can consider here. (footnote: I believe that civil resistance that intends to be a tool to push public support fits in this model; civil resistance that is purely about imposing physical cost operates in a different model).

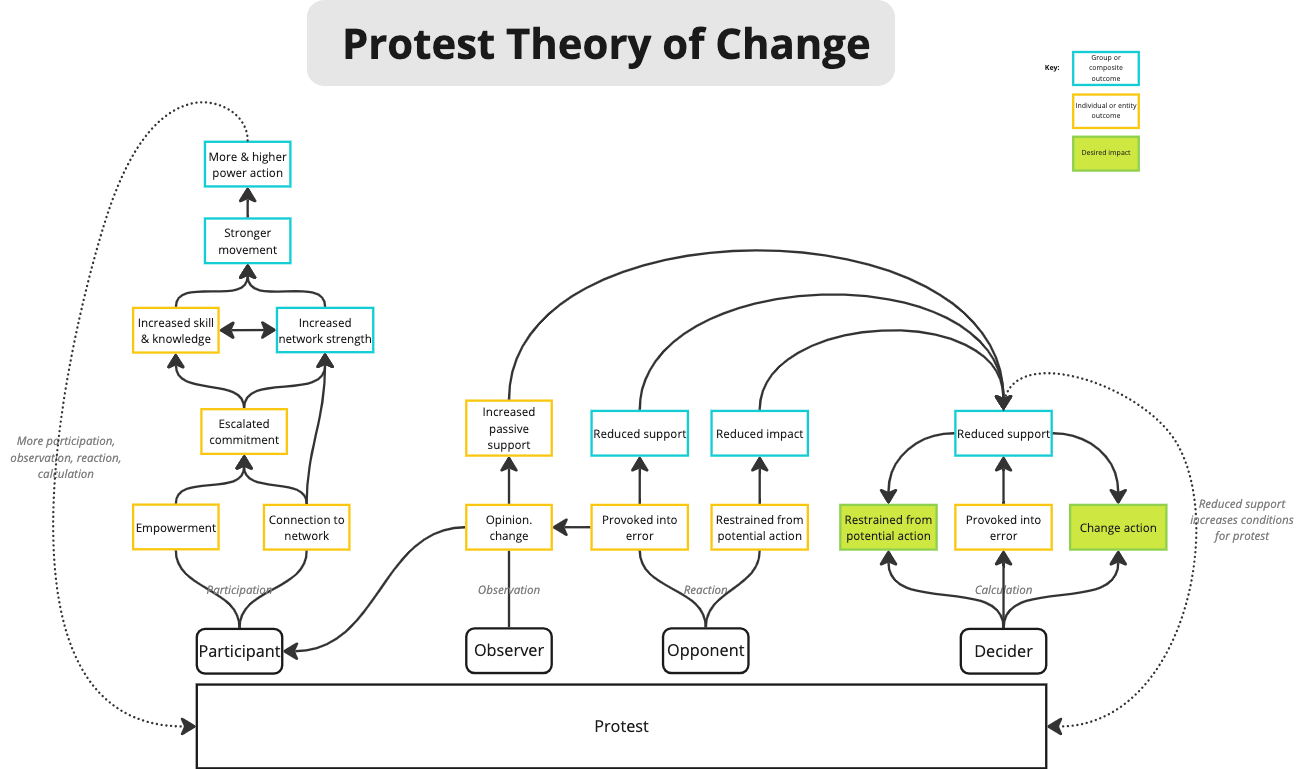

The theory states that protest action can produce real or perceived power sufficient to convince decisionmakers that meeting the demands of the protest action is the preferable course of action. Decisionmakers may predominantly make that calculation based on self-interest, but may also do so as a result of moral alignment (“it’s just the right thing to do”) or some larger ideological goal (a strategic sacrifice for some other end). In any case, our predominant model of protest relies on an alchemy between protest participants, observers, opponents, and the deciders – all of whom, in order for the protest to succeed, must behave in certain ways.

Participants:

By participating in protest, people are empowered to take further action and are connected to a network that will provide them the opportunity to do so.

By being connected to the network (a movement, organization, or other group), the person will increase their commitment through increased contact and collective expression of different forms.

Increased commitment will produce greater skills and knowledge for the person, as well as increased strength of the (larger) movement.

Stronger movements will be able to take more and higher power action, reproducing the desired effects of protest on observers, opponents, and deciders.

Observers:

People will observe protest action and change their opinions.

People will also observe any reactions to the protest action by opponents or deciders and change their opinions accordingly.

Low-level opinion change might result in attitudinal or passive alignment with the participants.

High-level opinion change might convert observers into new participants.

Opponents:

Opponents will observe protest action and respond to it.

Due to the protest, they may restrain themselves from potential action and thus reduce (a) the impact of their actions and possibly (b) their active support for the decider.

Due to the protest, opponents may overreact and alienate observers, pushing them towards the protestor’s cause.

Deciders:

Deciders observe protest action and calculate how to respond.

If the decider calculates the protestors could gain an unacceptable amount of power if an action is taken, the decider may refrain from taking that action.

If the decider calculates that the protestors have amassed sufficient power such that the status quo course of action will be less preferable than meeting the protestors demands, they will change the course of their action.

If the decider inaccurately calculates they can respond in opposition to the protest without significant consequence, they may reduce their own support by alienating observers and/or supporters.

Assessing the model

This theory of change is responsible for many of the great advances towards justice and equality of the modern era, including the 19th and 20th century fights to expand suffrage and civil rights. But in the United States of the 2020s, it is worth assessing if the frustration often found in this model — like that recent Saturday — is due to the quality and capacity of our protests or to structural barriers that are disrupting the model’s operation altogether. There are other accounts – such as “If We Burn” by Vincent Bevins” -- that speak to a larger question of why protest movements haven’t achieved their goals, including important aspects of organization, leadership, and hierarchy. I want to assess, more narrowly, why protest as a tactic at the center of a particular theory of change may be struggling.

Protest Quality or Model Breakdown?

Let’s consider common ways this protest model is interrupted or, worse, may damage movements:

Failure

No participation: People are not interested in participating in protest and do not participate.

No observation: Potential observers do not see protest (in person, online, in the news), so do not have opportunity to change opinion or join.

No reaction: Opponents ignore protests, denying them opportunity to increase observation and reducing opportunities for opinion change.

No calculation: Decisionmakers don’t recognize protest as a relevant variable in their calculation of power.

Damage

Disempowerment: Experiencing bad protest — whether boring, disorganized, or dangerous — disempower and demobilize potential members of a movement.

Negative polarization: Observers that witness protests that offend or threaten them may turn against or reduce support for a cause; protests can also raise the salience of issues to people who are already opposed to a cause, thus intensifying their opposition.

Counterattack: Opponents can use protest as a pretext for moving against a cause and seek to impose reputational, financial, legal, or physical damage that may be either unnoticed or sanctioned by observers.

Repression: Deciders, most often government, use protest as justification for crushing movements through law and force.

I am starting from the premise that these breakdowns, and a few in particular, are happening more often than they used to. This is an important premise to debate and I welcome challenges to the idea that this is the case. But proceeding from this assumption here, I want to open our inquiry from internal to external factors:

Are our protests small because we are bad at recruitment or because some tendency of contemporary behavior is anathema to that kind of social expression?

Are observers missing these protests because we’re not good enough at writing press advisories, or because there’s no longer a sufficient press to contact?

Are we unable to grow our audience because we aren’t presenting our content correctly, or because social media infrastructure is designed to concentrate our message among the same audience?

Are deciders calculating they can remain unmoved by our protests because they’re not big enough, or because popular support is now subservient to donor support in an unrestricted campaign finance system?

It’s worth evaluating all of these types of failure and damage and considering changing factors and contexts that may be increasing their prevalence. There are two parts of the model, in particular, that feel most urgent to confront now: (1) the connection between protest and observation, and (2) the relevance of protest to a decider’s calculation.

Protest and observation: The model requires some kind of mediation (pun intended) between the protest act and observers beyond those immediately present. We could imagine that media representations of 20th century protests both benefited from: (1) national news monoculture that concentrated audiences of diverse ideologies, (2) less ideologically stratified media, and (3) local news that actually, uh, existed. Social media initially seemed to be a stand-in for getting protest to potential supporters and allies, but changes in network design and usage may have undermined that capacity. Media and social media have partitioned content, and specifically political content, in ways that would lead protest content to be delivered particularly to people that already agree with and want to see it. Conversely, ideologically antagonistic media and social media now have disproportionate ability to represent protest negatively without any counternarrative (e.g. a media diet exclusively representing BLM protests as violent & destructive). Fundamentally: is there still a viable conduit between active participation and scaling to broader, mobilizable audiences? If at least viable – as the spread of both BLM and Gaza protests could suggest – is there a new limit to observation that could make this approach unstrategic? Even more worryingly, might leaders understand this phenomenon and bank on the fact that wide-scale repression won’t be widely visible and, thus, won’t result in mass outrage?

Deciders and calculating protest: Even in the circumstances where protests gain sufficient size or widespread support, there’s reason to question the corresponding value to changing a decider’s mind. The vast active and passive opposition from the Democratic base to its party’s support of the genocide in Gaza has seemed ultimately immaterial to Biden or Harris’ policy; 2020’s Black Lives Matter protests were the largest in American history and, in 2024, police are killing more people than ever before (among other metrics of failure). It is possible that in these and other cases protest movements just haven’t produced enough public support to force the hands of those in charge. But we should also consider that deciders may no longer consider protest and public support to be a relevant factor at all. In addition to repeated evidence of mass protest’s inefficacy – particularly if deciders are ready to wait it out – today’s unrestricted campaign finance environment may mean that electeds are balancing donors instead of voters.

So what

I am not necessarily convinced by these theories, just like I’m not necessarily convinced that smartphones and the Internet have irreversibly reduced the possible impact of IRL protest, but I do think we need to discuss them. If they prove reliable, everything will depend on getting to work — theoretically and practically — on alternative ways to push forward change.

Setting aside the more drastic idea of finding a new theory of change, I’m hoping that being explicit about the theory can at least allow us to be extremely precise and disciplined about when we are using protest and for what purposes (and when other methods of organizing or of action may be more appropriate). If this model still has power to offer us, we desperately need to take the time to figure out how to navigate it in improved and unprecedented ways.

What do you think? Share your perspective in the comments.